Micro metal-movers: MSU biochemists are one step closer to better cancer treatments

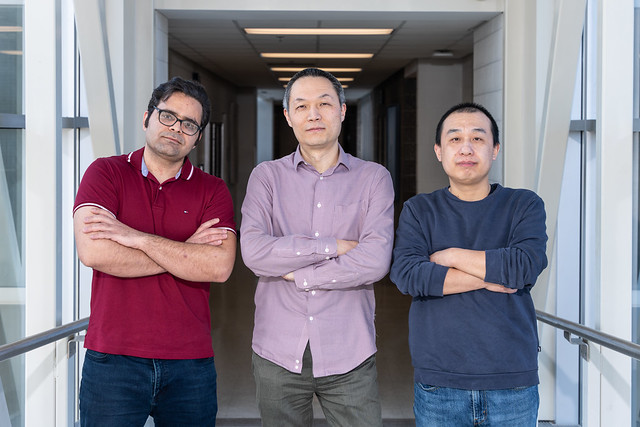

Led by Jian Hu and Kennie Merz, the MSU team has unveiled new insights into a family of proteins that, while vital for cellular functions, are also linked to an array of diseases such as breast, ovarian and pancreatic cancers.

Understanding these dynamic proteins found in cell membranes — called Zrt-/Irt-like proteins, or ZIPs for short — will contribute to the search for cutting-edge drug therapies and the improved health of patients.

“The hope is to develop an inhibitor against this protein,” said Hu, a professor in the departments of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and Chemistry.

Like experienced mountaineers leading hikers through tricky terrain, ZIPs guide metals such as zinc, iron and manganese into cells. A balance of these metals is crucial for our health but mutations in ZIPs can eventually cause a range of severe health issues.

Leveraging structural biology, biochemistry and cutting-edge computational simulations, Merz and Hu unpacked the complicated dance a ZIP protein found in the bacterium Bordetella bronchiseptica, or BbZIP for short, must perform so metal ions can reach their intended destination.

The unprecedented look into the molecular mechanisms of these crucial metal-movers was published in the journal Nature Communications.

“This is the most comprehensive understanding of this protein family yet,” Hu added.

Elevators and hinges

Transporting metal into a cell is a major feat of logistics. Metal ions are positively charged and hydrophilic (absorbs water), while the cell membrane’s is hydrophobic (repels water) and nonpolar, acting as a natural barrier.

“Transporters need to generate a pathway for the metal to successfully pass through the membrane,” Hu explained, noting that a ZIP will first face outward, allowing metal ions to enter a metal binding site inside the protein. Then, this metal binding site will face inward, releasing the metal into the cytoplasm.

In a first-of-its-kind discovery, Hu’s lab previously identified an elevator-like motion that BbZIP utilizes during this transportation process. With their latest publication, the Hu and Merz groups have added a literal twist to the story — in addition to an up and down movement, BbZIP also employs a hinge-like rotation as it ferries metal ions.

Pushing further, the Spartan biochemists also defined the pathways metals are most likely to take to be released into the cytoplasm. This included the discovery of an entirely new metal binding site.

To successfully capture the metal transport steps through the ZIP from start to finish, the researchers applied the specialties of both labs, using a diverse array of biochemical and computational approaches.

“This work was a strong collaboration between experimental and theoretical groups — that’s the power,” Merz said, a Joseph Zichis Endowed Chair in MSU’s Department of Chemistry and a quantum molecular scientist at the Cleveland Clinic.

Two paths diverged

Using metadynamics simulations, the Merz Group was able to visualize the movement of zinc ions through BbZIP using a set of highly specialized parameters. These parameters allowed the simulated protein and metal ions to engage in diverse and sometimes unexpected interactions.

“It was amazing to see just how dynamic the process was,” Majid Jafari said, a graduate student in the Merz group and an author on the latest paper. “Without our parameters in place, we saw the metal tended to stay mostly in a single binding site throughout the simulations — but once applied, the transport mechanism was facilitated, and we saw more frequent metal release.”

“There have been hints, but this is the first observation of the full sequence,” Merz added. “With these parameters, we were able to facilitate large scale, complex motions."

Simulating transportation pathways also revealed how zinc ions took a route through BbZIP that led to a newly discovered metal binding that the Hu group had experimentally identified. Surprisingly enough, this binding site was inhibitory, meaning that without it, metal ions would actually reach the cytoplasm inside the cell faster.

“It seems counterintuitive not to go the easiest way,” Hu said, but like many biochemical mysteries, the reason behind the mechanism could be a vital part of a cell’s fine-tuned machinery.

Though fundamentally important, transition metals such as iron, zinc, manganese and copper are also toxic and more reactive in biological systems. Hu believes that the newly discovered inhibitory binding site might be a metal sink — a key component that holds onto metal ions and helps avoid a rapid accumulation of the potentially toxic metals.

“Metal transport is a highly regulated process, and there’d be reason to have a break before the metal is released,” Hu added. “The metal sink plays a role in slowing this system down just a bit.”

With these findings, the Hu and Merz groups have broadened the horizon for experimental and computational investigations into ZIPs.

The better scientists understand the intricate choreography of metal ion transport, the better chance there are for therapeutic breakthroughs.

“We want to characterize more particular drug targets, what these protein structures look like, and what conformational changes occur,” Hu said, noting the promising frontier of ZIP-targeting medicinal chemistry underway.

- Categories: